The State of New Jersey has advanced policies, programs, and projects such as complete streets that encourage greater transportation modal choice and less dependency on the single-occupancy vehicle to address climate change and promote mobility and access for all users. The NJ Statewide Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan and Complete Streets policy seek to increase connectivity and micromobility safety through road diets and other infrastructure changes. New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) is also sponsoring safety programs that aim to reduce traffic related fatalities. In-depth research that looks at differences across gender, race, socioeconomic status and ability may assist in expanding policies and statewide initiatives that prioritize safety and accessibility for all road users.

This Q&A article has been prepared following an interview with Dr. Hannah Younes, a post-doctoral researcher at the Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center at Rutgers University, who focuses on cyclists and e-scooter behavioral patterns. Her most recent study conducted in Asbury Park, NJ observed gender differences of chosen micromobility mode, helmet usage, and location. We interviewed her to better understand the data sources and methods used in the research, its limitations and explore the applicability and implications of her research findings to the field of transportation and future research. The Q&A interview has been edited for clarity.

Q. How was your research funded?

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under a grant called “Making Micromobility Smarter and Safer”. The lead on this is Dr. Clint Andrews at Rutgers University and there are several other principal investigators. My study acts as a part of this multi-year research.

Q. Can you share a brief overview of your findings? Are the results surprising or unique compared to past research?

We are one of the only studies comparing the safety behavior of cyclists and e-scooter users across genders. Without considering gender, we found that one-third of cyclists wore a helmet. We also found in our observations that e-scooter users did not wear a helmet. It speaks to how important it is to have safe micromobility infrastructure, especially knowing that people are unlikely to wear a helmet. In the U.S., even if you give everyone a helmet, they’re probably not going to wear it. That’s just how it is. Keeping people safe in other ways is paramount.

We also found that a greater proportion of women were using e-scooters than bicycles. This is important because cycling has long been a male-dominated mode of transportation, for a variety of reasons. That is true across the world. There are studies that suggest women are less likely to cycle to work because of clothing like wearing a skirt or dress or heels, or fears of sweating. E-scooters remove that hurdle since they are not as prohibitive in terms of clothing and require less physical exertion. So, the vehicle type itself may make a difference. Moreover, women place more importance on bike lane infrastructure than men. If we are seeing that e-scooters are the preferred mode for females, perhaps e-scooters can help narrow the gender gap in micromobility.

Q. Can you talk a little bit about the methods used for this study? How are these methods different from past research? Why did you choose to use traffic cameras for your observations?

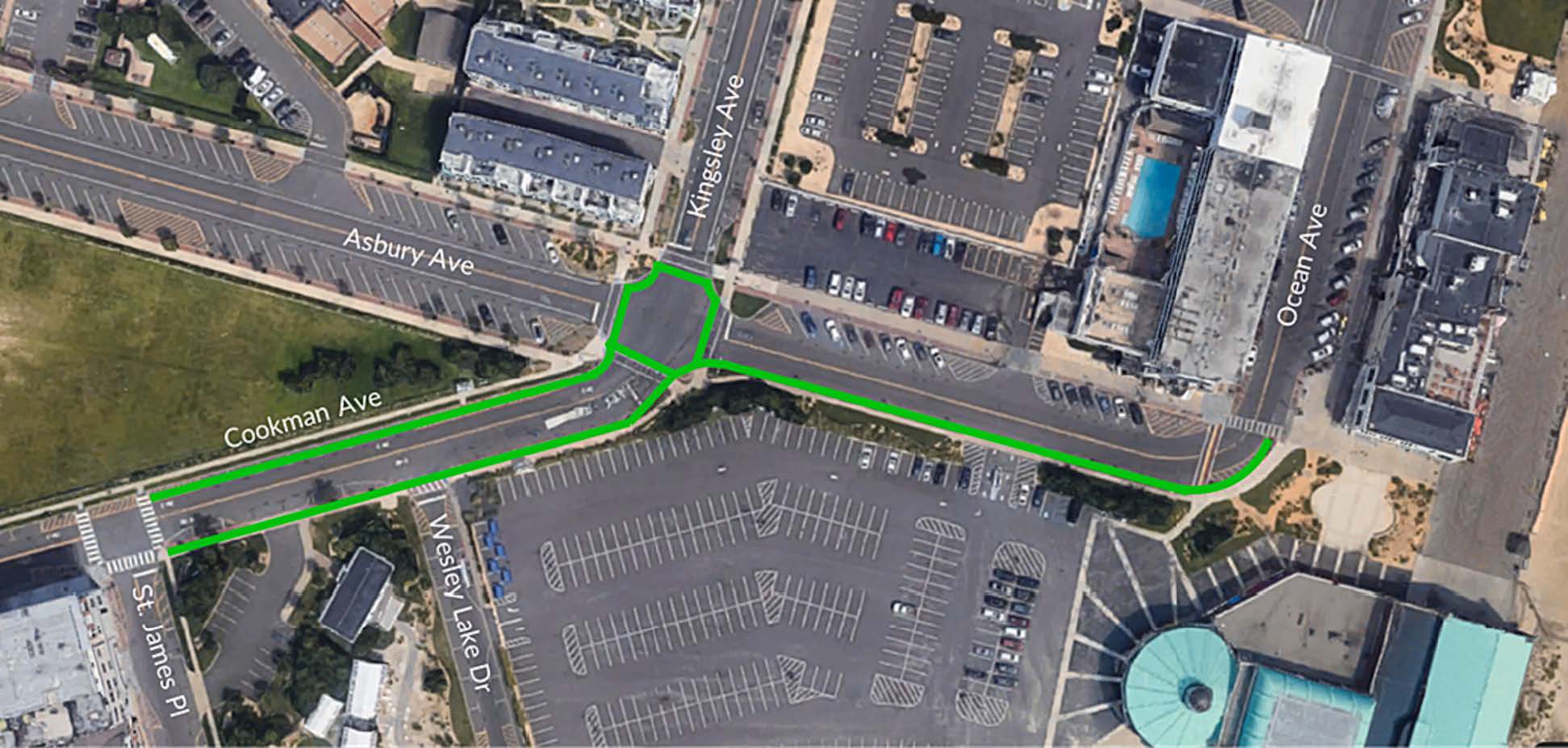

This work was done using manual observations, a common method in micromobility studies. Previous research had used observations collected in the field. Instead of having observers in the field, we observed traffic camera footage at one intersection. Because we were observing gender and race as well as group behavior, the footage was useful as it allowed us to pause when needed. It was also less resource intensive than having a person stand in the field since no travel expenses were associated with the analysis.

Q. What challenges have you found in working with and interpreting traffic camera footage? With the improvement of AI technologies, do you think there will be an opportunity to automate this process in the future? Are there any limitations you expect from this type of innovation?

It is very time consuming and tedious to analyze this much camera footage. We analyzed 35 hours of footage. I would love to have analyzed more, but you have to draw the line somewhere depending on the resources available for the research or project study. Most of the time, we fast forwarded until a micromobility user was detected, but it still requires undivided attention. There is a possibility with current technology to incorporate AI technologies: to use computer vision to detect humans, which then can be manually viewed by a human to assess micromobility mode, gender, and helmet use. This would likely reduce the manual labor… It would be interesting to compare the computer vision model to the work I have done… Nonetheless, computer vision does not differentiate properly between pedestrians and e-scooter users, so it is prone to misidentification, which would lengthen the time taken to observe manually.

At this point, computer vision cannot detect gender, helmet use, and group riding properly from traffic camera footage. More high-resolution images would be needed to differentiate gender and helmet use (like unobstructed face images) and group riding requires context clues like making eye contact, waiting for one another, etc. AI has the potential, but it is not there yet. As time consuming as it is, I am confident that we detected every person, which is why we chose to observe the footage ourselves.

Q. What are the limitations of this study? Do you have plans for future research to address these? How would you like to expand your research on this topic?

The main limitation is the geographical scope of this research; it’s a lot of work for one city. We only analyzed the behavior of micromobility in one location, Asbury Park. It isn’t clear how much the results will translate from one location to another. Mode of transportation and behavioral use depends on many different factors that vary from location to location. There is evidence that the gender gap is smaller for e-scooter users in Brisbane, Australia, but not to the extent observed in Asbury Park. Same goes with helmet use. A larger scale study would be useful. Other limitations include the types of micromobility modes: we only observed shared e-scooters and privately owned bicycles in Asbury Park. So, we’re comparing two different vehicles and two different share types to one another. When analyzing the data, we must consider both of these factors. For example, are behaviors attributed solely to the vehicle or to the share type? Probably both. When you’re looking at the gender gap, is it because it’s an e-scooter or is it because it’s shared that there is a narrower gender gap?

An analysis comparing shared and privately owned e-scooters with shared and privately owned bicycles would be great. Differentiating between e-bikes and bicycles would be great too, although the resolution of traffic camera footage makes it very hard to differentiate between the two. Even with an observer onsite, it would be hard to detect, so you would need a survey, but this could alter behavior. In Asbury Park, a lot of people have privately owned e-scooters now, so we could do another study in 1.5-2 years and get additional insights in the same location.

E-bikes are a growing mode of transportation, but even with traffic camera footage, it is very hard to tell an e-bike apart from a bicycle, so maybe in that case you would need somebody on site actually observing. You’re losing the ability to pause footage, but it might be more useful if you’re looking at e-bikes. Race and age were also very difficult to observe from the footage. It could be easier if someone was in person to observe in addition to the traffic camera footage. Even then, without asking directly the age and race/ethnicity of the user, there will be bias. There are a lot of different things to consider; it really depends on what the question is.

Q. How would you like this research to inform transportation agencies and practitioners in New Jersey and elsewhere?

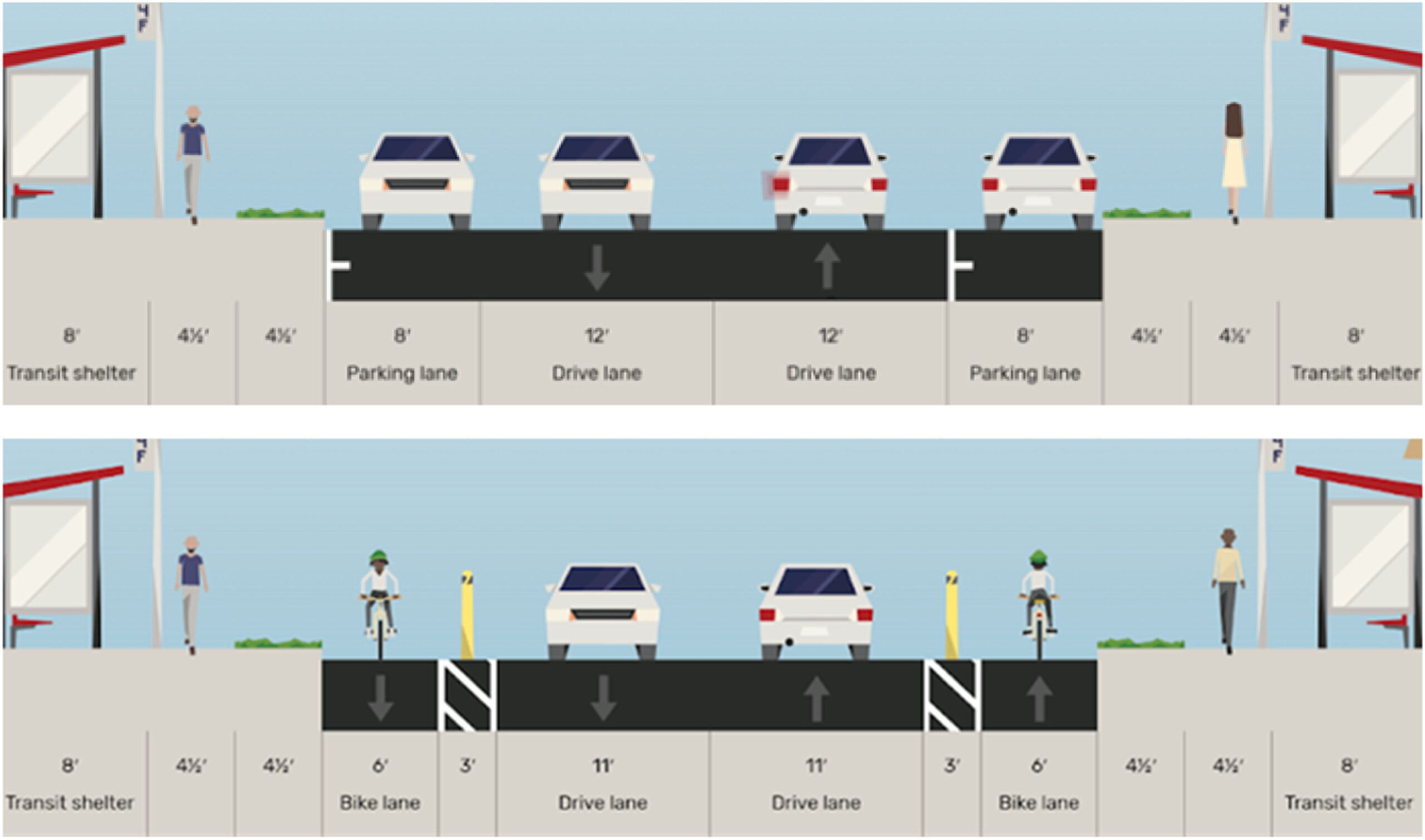

There are several key points. Users of shared e-scooters and privately owned bicycles are different and behave differently. E-scooter users are more likely to take risks like not wearing a helmet or riding on the road. Planners must ensure that the infrastructure keeps them safe. That is, implementing dedicated protected bike lanes that are connected to a greater network and adding traffic calming measures to slow the speeds of motor-vehicles like raised crosswalks or narrower traffic lanes.

Understanding the reasons behind lane use is important as well, as there are concerns for pedestrian safety. Our research observed that lane use was different; for example, 7 percent of male cyclists rode on the sidewalk, compared to 28 percent of female e-scooter users.

Additionally, having a shared e-scooter system in a city can increase female participation in micromobility use. It is a more gender equitable mode than bicycles. Other agencies might want to implement an e-scooter share program in their town.

Q. Your research shows that women were more likely than men to ride on the sidewalk while using an e-scooter or bike. Given that this strategy is illegal in most parts of the country, how can planners, engineers and policymakers use this information to increase feelings of safety for female micromobility users?

This is really interesting. From my research, there is not a lot that I could say. Implicitly, one of the reasons for someone to ride on the sidewalk instead of the road is that they feel safer on the sidewalk. There is a need to ensure that micromobility users feel just as safe on the road–that is, implement a dedicated and protected bike lane, and provide a clear separation from motor-vehicles.

From our work, we know that there are other more complex factors at play: our research had clear results for road lane use with the implementation of the bike lane, but less clear ones for sidewalk use: sidewalk use was not significantly reduced by the presence of a pop-up bike lane. To encourage safe road use, ensuring a complete network would be a start. The pop-up bike lane was not connected to another bike lane going downtown, for instance. If you’re already coming downtown on the sidewalk, you might be more likely to stay there given the existing curb that would need to be crossed to go from the sidewalk to the pop-up bike lane.

Q. NJDOT is sponsoring a program to ensure the implementation of the Statewide Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan. In what ways could this master plan or a future one align with the findings in your study?

The results of this study reinforce that implementing a bike lane provides a layer of safety for micromobility users. Nearly all the increase in bike lane usage came from a reduction in traffic lane usage, not in sidewalk usage. There is so much research out there that shows that bike lanes save lives; in the case of a crash, someone in a bike lane is less likely to be injured. Ensuring that plans accommodate both bicycles and e-vehicles–like e-bikes and e-scooters–is also paramount.

Q. The Biden Administration has set a goal to achieve a net zero emissions economy by 2050. How might a shift toward micromobility help the nation reach its climate and carbon emission goals?

Bicycles are zero emission vehicles. E-bikes and e-scooters produce few emissions, especially privately owned ones since they don’t require rebalancing. Rebalancing shared vehicles requires a car or van and those gasoline emissions are absorbed by those shared e-scooters. Having an e-vehicle do that for rebalancing helps to reduce those emissions. Bicycle-friendly infrastructure, which reduces motor-vehicle infrastructure such as the number of traffic lanes, or parking, can also reduce motor-vehicle use and induce more environmentally friendly travel.

Q. How could a focus on reaching these climate goals impact the way that planners and engineers design streets?

Motor-vehicle travel is the most polluting transportation mode. A shift towards micromobility Infrastructure, particularly in cities, can help induce travel from eco-friendly modes and reduce motor-vehicle use. This should be in conjunction with other measures, such as increasing gasoline prices, increasing parking costs, and providing subsidies for eco-friendly modes.

Resources

Blickstein, S.G., Brown, C.T., & Yang, S. (2019). “E-Scooter Programs Current State of Practice in US Cities.” Retrieved from https://njbikeped.org/e-scooter-programs-current-state-of-practice-in-us-cities-2019/

Marshall, H. (2023). “How do Female Cyclists Perceive Different Cycling Environments? – A Photo-elicitation study in Stockholm, Sweden.” Retrieved from https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/78209

NJDOT Technology Transfer. (2020). “Tech Talk! Launching Micromobility in NJ and Beyond.” Retrieved from https://www.njdottechtransfer.net/2020/02/25/launching-micromobility-in-nj-and-beyond/

NJDOT Technology Transfer. (2021). “How Automated Video Analytics Can Make NJ’s Transportation Network Safer and More Efficient.” Retrieved from https://www.njdottechtransfer.net/2021/11/08/automated-video-analytics/

NJDOT Technology Transfer.(2022). “Research Spotlight: Exploring the Use of Artificial Intelligence to Improve Railroad Safety”. Retrieved from https://www.njdottechtransfer.net/2022/08/19/researchspotlightairailroadsafety

Rupi, F., Freo, M., Poliziani, C., & Schweizer, J. (2023). “Analysis of Gender-Specific Bicycle Route Choices Using Revealed Preference Surveys Based on GPS Traces.” Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0967070X2300001X

Salazar-Miranda, A., Zhang, F., Maoran, S., & Ratti, C. (2023). “Smart Curbs: Measuring Street Activities in Real-Time Using Computer Vision,” Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169204623000348?casa_token=XPecGlOM6UQAAAAA:vnISsmV2aoJ3iVJefEeqjM24R5izcs66bvukCQObjuSWGTNokotT4CG_1h8UfLih16wn3FMg_Jo [DA1] [KR2]

Von Hagen, L.A., Meehan, S., Younes, H., et. al. (2022), “Asbury Park Bike Lane Demonstration,” Retrieved from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/c014811ac0c14735bc9c9adc2639e88f.

Younes, H., Noland, R., & Andrews, C. (2023). “Gender Split and Safety Behavior of Cyclists and E-Scooter Users in Asbury Park, NJ,” Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213624X2300127X#b0055.

Younes, H., Noland, R., & and Von Hagen, L.A. (2023). “Are E-Scooter Users More Seriously Injured than E-Bike Users and Bicyclists?” Retrieved from https://policylab.rutgers.edu/are-e-scooter-users-more-seriously-injured-than-e-bike-users-and-bicyclists/.