Concrete production is energy intensive, and requires materials that are both challenging, and expensive to acquire. Material engineers are seeking alternative materials that are more cost-effective and carbon-friendly, but also operate successfully as road and building material.

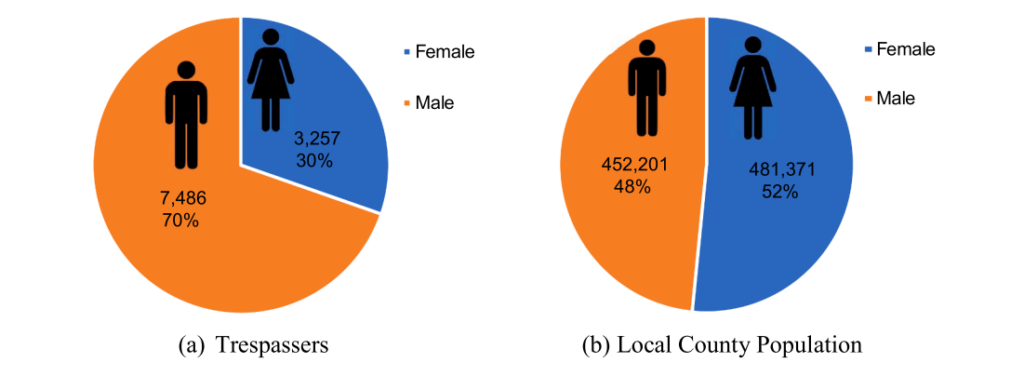

We spoke with Alyssa Yvette Sunga, a graduate researcher at Rowan University who won the Best Student Poster Award at NJDOT’s 2023 Research Showcase. Her research, “Properties of Cementitious Materials with Reclaimed Cement,” evaluated the characteristics of cementitious materials mixed with varying percentages of reclaimed cement. Sunga and her fellow researchers examined each mixture’s initial setting time, heat of hydration and compressive strength and compared it against ordinary Portland cement. The purpose: to determine if adding reclaimed cement has any effect on the durability and use of cementitious materials. If there is little to no adverse effect, reclaimed cement may help reduce the need for new materials and can reduce the carbon bi-product of concrete. Dr. Shahriar Abubakri (Shah), Ms. Sunga’s supervisor at Rowan University, also joined us for the interview.

Q. Could you tell us a little bit about your educational and research experience and how you got where you are now as a graduate research fellow at Rowan?

A. I’m an international student from the Philippines. I graduated from the University of the Philippines – Los Banos in 2017 with a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering. After that, I worked in industry from 2018 to 2022. My former undergraduate professors, who were graduate students here [at Rowan], reached out to me asking if I was interested in pursuing graduate studies. I applied and began my Master’s in Civil Engineering in January 2023.

Q. What interested you about researching the properties of reclaimed cement? Do you hope to continue research in pavement materiality?

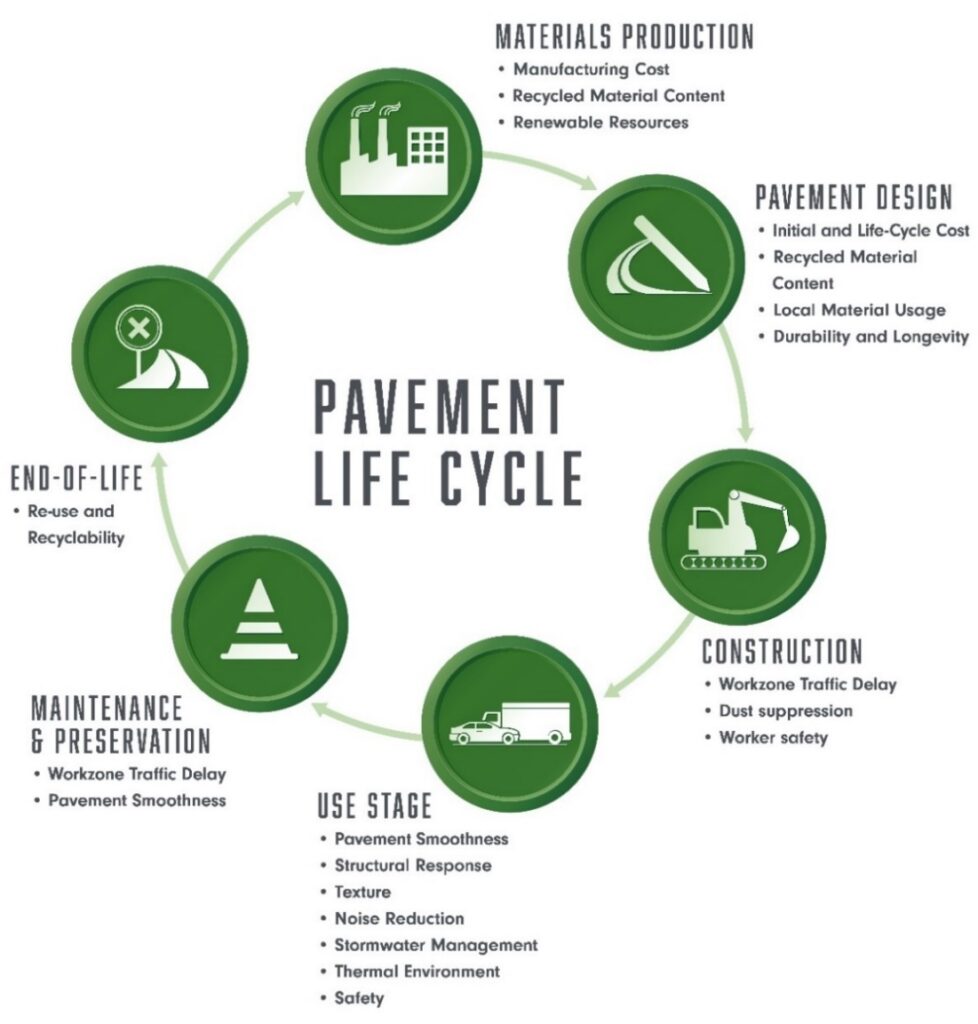

A. The environmental impact of reclaimed materials like cement is interesting to me. Cement production is a significant contributor to carbon emissions, so finding ways to reuse it is essential. Additionally, reclaimed cement presents unique challenges and opportunities in terms of material properties, durability, and performance.

So, in a way, we’re helping produce less carbon emissions; that’s what interested me about this study.

I’m currently working on a lot of different concrete projects. We’re hoping to develop more efficient construction approaches, but I also aim to contribute to the development of innovative techniques and solutions that will optimize reclaimed materials in construction projects. We also aspire to collaborate with industry partners and government organizations, so that we can implement these sustainable practices on a full-scale project in the future.

Q. Was there anything particularly noteworthy or surprising to you discovered from this research?

A. Yes, there’s potential for reclaimed cement and enhancing the performance of unsustainable construction materials. We did not expect that we could use it as a replacement cement or as a supplementary cementitious material. Through various experiments, we found that using this reclaimed cement or incorporating it in cementitious mixtures resulted in comparable properties such as durability, strength, and workability.

Q. Your research looked at cement paste and mortar specimens incorporated with up to 20% Reclaimed Cement and found no significant difference for the flow measurement and setting time. Should further research be done with higher percentages of reclaimed cement? Why did your research cap it at 20%?

A. We’re planning to do further research on larger amounts of reclaimed cement. We just used 20% as a cap to get a general idea of the effect of partially replacing ordinary Portland cement with reclaimed cement. Now that our research with 20% is showing good results, we plan on doing tests with higher percentages in the future.

Q. Your research found that cement paste specimens with up to 20% Reclaimed Cement (RC) saw a 4% reduction in compressive strength after 90 days. What does this mean for applicability (i.e. is 4% a significant reduction? does this make cement paste with 20% RC not suitable for pavement?)

A. A 4% reduction may seem small, but it must still be taken into consideration. However, as long as the strength is within a recommended range, then it is suitable for pavement applications.

Q. Is there a percentage of reclaimed cement that is most likely not suitable for pavement?

A. Alyssa: My advisor would like to jump in to answer that.

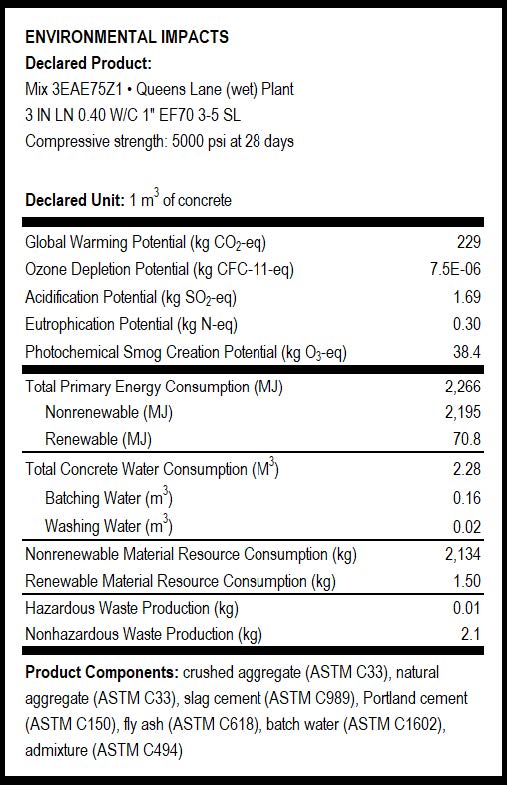

Shah: The acceptable percentage of reduction in concrete strength depends on the specific application and the assumptions made by the designer. For instance, practical standards like the American Concrete Institute (ACI 301.1.6.6) typically require that the average strength of three samples meets or exceeds the specified compressive strength. Additionally, each individual sample within this set should not fall below 500 psi of the designed strength. It’s important to note that concrete’s compressive strength can vary widely, ranging from 2500 psi to 5000 psi, and even higher in residential and commercial structures. Some applications may require strengths exceeding 10,000 psi. So, in cases where the required strength aligns with the design strength, even higher reductions may be acceptable.

Q. Mortar specimens with 20% RC had a different result and surpassed the strength after 28 days. Why do you think this was a different result from cement paste specimens? What does this mean for applicability?

A. This difference in result may be due to different factors, but mortar differs from cement paste due to the additional materials like sand. So, this can influence the hydration and the strength development, but we still need to do further research to understand the long-term performance and durability or the effect of adding different materials to the cementitious materials.

We still must do further research to see the effects of adding different materials like sand and gravel to cement paste. If we’re going to use it in concrete, that’s another additional material like an aggregate. It’s just a matter of the specific materials. There are a lot of factors — like the temperature where you make your specimens. So, it’s always just trial and error. There’s no trend to it really.

Q. Your poster suggests that incorporating up to 20% RC has some promising benefits including reducing carbon emissions. What are some of the other benefits?

A. Incorporating the 20% RC will help mitigate supply shortages because we’re able to provide an alternative source of material instead of just using cement. It also promotes eco-friendly construction practices, contributing to sustainable transportation infrastructure, and research on reclaimed cement enables ongoing enhancements in material performance and construction methods.

Q. You have mentioned throughout this interview where there’s a need for more research. Can you describe some specific things that you would really like to research about incorporating reclaimed cement into cementitious materials?

A. The most important part of this research is determining what is the optimal mix proportions to use and then studying the effects on fresh properties and assessing the long-term durability like compressive strength, the tensile strength. These investigations are crucial for understanding the full potential of reclaimed cement in construction. Personally, I’m deeply interested in exploring these research areas further.

Q. What kind of impact do you hope this research will have on material selection by transportation agencies?

A. I hope this research convinces transportation agencies to use reclaimed cement in pavements. It’s sustainable, cost effective and performs well — aligning with transportation agencies’ goals and standards. This could lead to a greener and more resilient transportation infrastructure.

Resources

Sunga, A., Abubakri, S., Lomboy, G., Mantawy, I. (2023). “Properties of Cementitious Materials with Reclaimed Cement”. Rowan University Center for Research & Education in Advanced Transportation Engineering Systems. Poster.

Yvette Sunga, A., Abubakri, S., Lomboy, G., & Mantawy, I.M. (2024). Properties of Cementitious Materials with Reclaimed Cement. Presented at IABSE Symposium: Construction’s Role for a World in Emergency, Manchester, United Kingdom, 10-14 April 2024, published in IABSE Symposium Manchester 2024, pp. 428-434. Retrieved at: https://structurae.net/en/literature/conference-paper/properties-of-cementitious-materials-with-reclaimed-cement

For more information about the 25th Annual NJDOT Research Showcase, and to see other award-winning posters, visit: Recap: 25th Annual NJDOT Research Showcase – NJDOT Technology Transfer (njdottechtransfer.net)