The U.S. Department of Transportation recently announced $2.2 billion in project funding awards for the Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) program for 2022. The 2022 RAISE grants are for planning and capital investments that support roads, bridges, transit, rail, ports, or intermodal transportation. The RAISE program received a significant increase in its funding due chiefly to additional allocations afforded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (also known as IIJA or the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law).

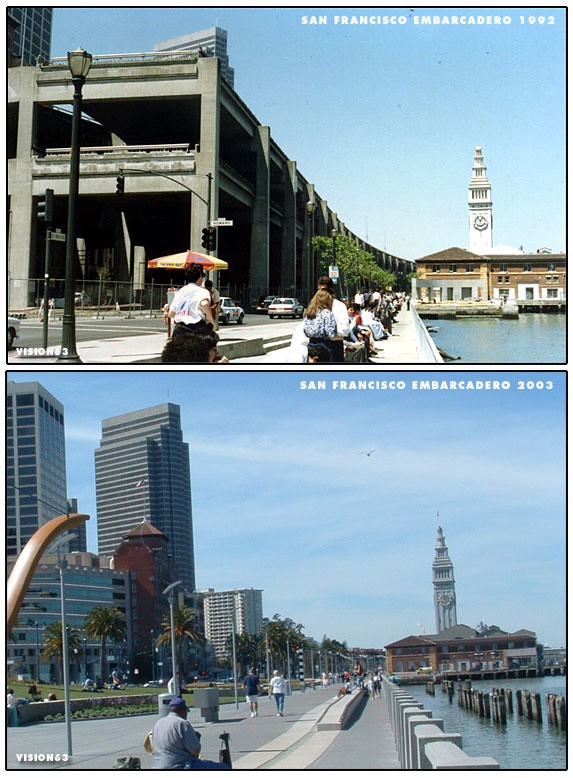

Chris Coes, FHWA’s Assistant Secretary for Transportation Policy, highlighted in a press release that 52 percent of the RAISE funding in the current round was for roadway projects with a substantial amount of that intended for “Complete Streets” projects — that is, pedestrian-friendly renovations to existing roadways (1). Complete Street initiatives, such as San Francisco’s RAISE-funded introduction of concrete buffers and protected bike lanes to Howard Street (2), are expected to create safer, more equitable communities where the automobile has disrupted livability. RAISE can likewise leapfrog funds directly to local governments and metropolitan planning organizations in this pursuit.

RAISE’s funding is a major break from its predecessor program in its greater support for modal diversity and the application of the equity lens in project prioritization. According to the Urbanist, transportation analyst Yonah Freemark claims “that just 10% of the dollar amounts [of RAISE’s 2022 budget is] set to fund projects that build new roadways or expand existing ones” (3). For comparison, BUILD (a Trump-era successor to the Obama-era TIGER program) devoted roughly 50 percent of its funds toward expanding and building new automobile roadways (3). Additionally, 50% of RAISE funding will go to rural communities (1) and roughly two-thirds will go to areas of persistent poverty or historically disadvantaged communities (1), ensuring equity is a centerpiece of RAISE.

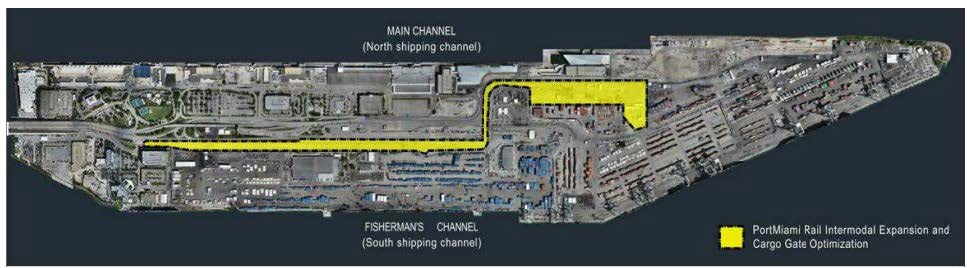

In the current funding round, the US DOT has announced 166 projects that are receiving RAISE funds with roughly 7 percent of the competitive funding program going to maritime projects and 4 percent for rail (1). Environmental Justice considerations and equity concerns are intertwined with port intermodal projects such as the “Port Miami Net Zero Program” in Florida, which will expand its intermodal rail capacity, add electric cranes, and improve its stormwater drainage system (2). Often diesel powered infrastructure at port facilities or vehicular traffic along highways can emit harmful air pollutants into nearby vulnerable communities; in this context, RAISE investment in port, rail, and vehicle electrification may yield a reduction in the environmental harms borne by nearby populations and communities.

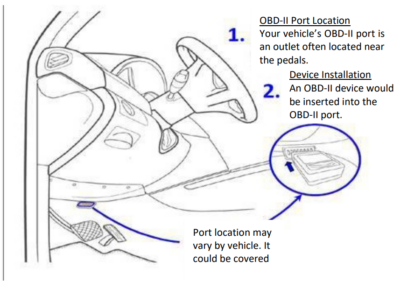

Physical barriers or guard poles funded through RAISE will address safety inequities affecting cyclists. Courtesy of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

Planned RAISE-funded renovations combine improvements to efficiency and equity with greater investment in sustainable, greener technologies at America’s ports and in other transportation systems. Courtesy of U.S. Department of Transportation.

RAISE 2022 Factsheets show that the planned ferry route between the City of Elizabeth and Manhattan will also take advantage of connections between Elizabeth’s waterfront and Newark Liberty Airport. Courtesy of U.S. Department of Transportation.

In a similar vein, a $5 million RAISE planning grant to the City of Elizabeth will examine, identify and assess the feasibility of an electric ferry service from the Elizabeth, NJ waterfront to New York. The envisioned project would provide a ferry terminal and ferry service to and from Manhattan (2). Beyond studying the congestion and carbon emission reductions and energy savings from such infrastructure for NJ-NYC commutes, the RAISE planning grant to Elizabeth will also analyze the land development and economic impacts of project enhancements to the municipality’s waterfront (2). With the potential implementation of “cordon-based” congestion pricing in Manhattan, the Elizabeth ferry service might provide more affordable access, or another mass transit travel option to reach NYC’s employment centers or its entertainment and recreational destinations for New Jersey residents (4) in the face of steeper priced travel by auto.

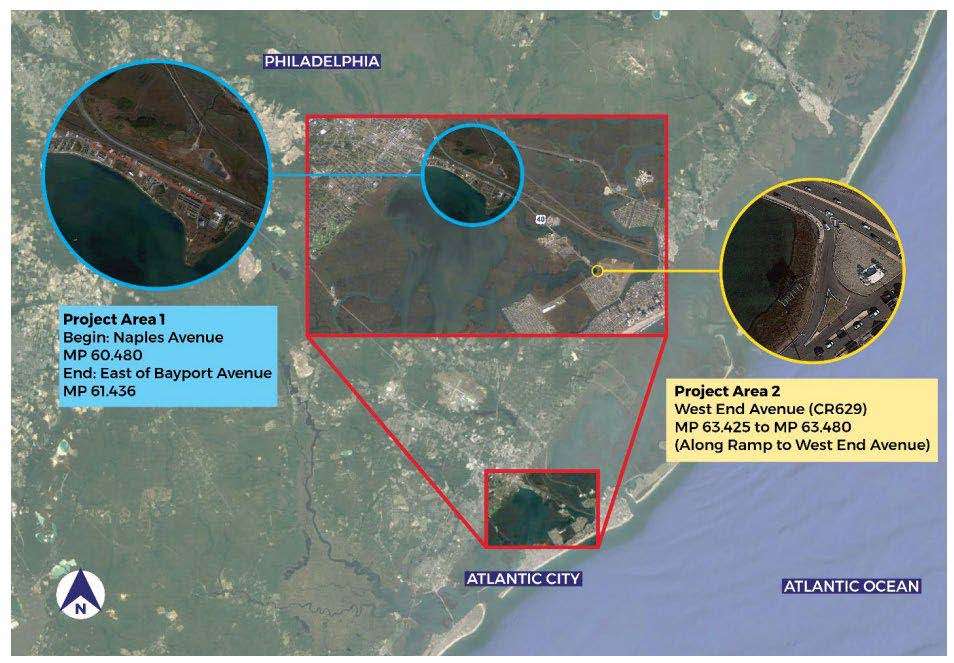

In New Jersey, the Atlantic City Resilient Route 40 Project was awarded $20 million in RAISE funding. Preparing for rising flood risks, the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) seeks to elevate one of Atlantic City’s main evacuation routes for vehicles and pedestrians, improve storm drainage in the busy Route 40 corridor, and relocate associated utilities (2). Thousands of commuters use Route 40 to reach their employment in Atlantic City’s casino industries (2). Reducing floods to vulnerable Route 40 paths will prevent low-income travelers from being forced to take the Atlantic City Expressway Toll Road as an alternative (2). NJDOT’s drainage efforts are no less important to the environmental equity aims of the RAISE-funded project; it is commonly found that the socioeconomically marginalized tend to live and work in areas of increased flooding risk. The inclusion of an updated 800-foot extension of an Atlantic City seawall and roadway drainage improvement will reduce hazards that would likely impact disadvantaged residents most directly.

Addressing Atlantic City’s coastal vulnerability with the RAISE-funded resiliency project could have measurable benefit to insurance rates for flood-vulnerable residents in addition to managing potential hazards. Courtesy of U.S. Department of Transportation.

Over the next five years, the RAISE program is expected to provide $7.5 billion in planning and capital improvements for transportation projects. Under this competitively awarded program, projects should be aligned with key project selection criteria, including safety, environmental sustainability, quality of life, economic competitiveness and opportunity, partnership and collaboration, innovation, state of good repair, and mobility and community connectivity (1). Within these areas, the U.S. DOT Department has emphasized that project selection will consider how projects improve accessibility for all travelers, bolster supply chain efficiency, and support racial equity and economic growth – especially in historically disadvantaged communities and areas of persistent poverty (1).

The RAISE program is just one of several programs that U.S. DOT has identified as covered by the Biden-Harris Administration’s Justice40 Initiative. The objective behind the Initiative is to address decades of underinvestment in disadvantaged communities and bring more Federal resources to communities most impacted by climate change, pollution, and environmental hazards (5).

Recent growth in available federal funding for transportation projects, including funding programs like RAISE, signal that the national transportation ecosystem can be reshaped — to some extent — through intentional planning, project selection, design and funding that looks to redress equity gaps and foster community livability and environmental sustainability The nation’s disadvantaged communities — defined in Justice40 through several indicators that map and measure economic condition, health, transportation access, environment, resilience, and equity — stand to gain from this greater commitment to the equity and opportunity lens in decisionmaking, and RAISE-funded projects are one means for actualizing this transformative objective.

REFERENCES

(1) Planetizen. (2022, August 11). $2.2 Billion in RAISE Grant Funding Announced for Transportation Projects. https://www.planetizen.com/news/2022/08/118257-22-billion-raise-grant-funding-announced-transportation-projects

(2) U.S. Department of Transportation. (2022, August). RAISE 2022 Fact Sheets. https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2022-08/RAISE%202022%20Award%20Fact%20Sheets.pdf

(3) The Urbanist. (2022, August 17). RAISE Grants Move Away From Road Expansion, But Not In Seattle Metro. https://www.theurbanist.org/2022/08/17/raise-grants-move-away-from-road-expansion-but-not-in-western-washington/

(4) TapInto. (2022, March 2). Coming Early This Summer: Elizabeth Fast Ferry to New York City. https://www.tapinto.net/towns/elizabeth/sections/business-and-finance/articles/coming-early-this-summer-elizabeth-fast-ferry-to-new-york-city

(5) U.S. Department of Transportation (2022, September 9). Justice 40 Initiative. https://www.transportation.gov/equity-Justice40